- Home

- Harold R. Johnson

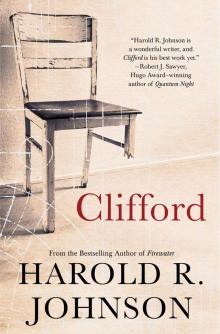

Clifford

Clifford Read online

Also by Harold R. Johnson

Fiction

The Cast Stone

Corvus

Charlie Muskrat

Back Track

Billy Tinker

Nonfiction

Firewater: How Alcohol Is Killing My People (and Yours)

Two Families: Treaties and Government

CLIFFORD

a memoir

a fiction

a fantasy

a thought experiment

HAROLD R. JOHNSON

Copyright © 2018 Harold Johnson

Published in Canada and the USA in 2018 by House of Anansi Press Inc.

www.houseofanansi.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author’s rights.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Johnson, Harold, 1957–, author

Clifford : a memoir, a fiction, a fantasy, a thought experiment /

Harold R. Johnson.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4870-0410-1 (softcover).—ISBN 978-1-4870-0411-8 (EPUB).—

ISBN 978-1-4870-0412-5 (Kindle)

1. Johnson, Harold, 1957–. 2. Authors, Canadian (English)—21st

century—Biography. 3. Autobiographies. I. Title.

PS8569.O328Z46 2018 C813'.6 C2018-900343-X

C2018-900344-8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018934053

Book design: Alysia Shewchuk

Cover design: Alysia Shewchuk

Cover images: (chair) Ragnar Schmuck/Getty Images; (blueprint) Jason Winter/Shutterstock.com

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

This humble work is dedicated to my older brother Clifford Melton Johnson. His earliest and lifelong ambition was to be a scientist, to think beyond the boundaries of his place of birth, and to explore ideas even larger than his home planet. To Clifford’s children, Clifford Jr., Brian, and Daniel: it is my hope to honour your father.

And, of course, to my father, Hildor Johnson,

and my mother, Mary Elizabeth Johnson,

who are equal parts of my story.

“Deep in the human unconscious is a pervasive need for a logical universe that makes sense.

But the real universe is always one step

beyond logic.”

From “The Sayings of Muad’Dib”

by the Princess Irulan

— Frank Herbert, Dune

Home

The chair stands on three legs, the fourth broken off and missing. It defies logic, defies gravity. I wonder whether it was the chair. Is that the one? It had once been a pale shade of green that was common in the fifties. Now most of the paint is gone and the wood has turned grey with age.

Is that the one he sat in?

I turn away. That isn’t the memory I came here to recover. The old house seems determined to continue standing, despite carpenter ants, wood rot, squirrels, mice, and birds. One whole corner of the ceiling sags, mouldy and water stained. Against the odds a single pane of glass remains in the west window; the other three, the victims of slingshots and mischief. The sunlight through the window sparkles on a broken shard before it strikes a floor littered with mouse droppings and squirrel mess. That floor had once been covered with shiny new linoleum.

There are memories here that I want to remember; the linoleum is one of them. It’s a gentle memory of not much consequence.

They’d brought the new flooring home, moved all the furniture outside, rolled the linoleum out, and tacked it down around the edges. It covered the trap door that led to the cellar, and we had to wait until it was worn and the imprint of the door showed through so that my father knew where to cut it.

I remember Mom’s cellar. The whole floor sags toward the centre of the room, and I don’t trust it to carry my weight. If the joists weren’t so rotten, it might be interesting to open it up and have a look down there. It won’t be much. Just a sandpit and plank shelves. But those shelves — the memory eases back — once held exactly a hundred jars. Canned blueberries, cranberries, strawberries, saskatoon berries, gooseberries, currants, raspberries, canned moose meat, canned fish. Everything she could preserve went into jars and down into that cellar: pickled carrots, green tomato relish, canned beets.

There’s something about smells and memory; I’d heard somewhere that the two work together. I am probably smelling only mould, but my memory is of a huge bin of potatoes and sawdust. I remember turnips and cabbages.

I remember the ladder and I remember brothers.

Clifford came running into the house, and the cellar door was open. He fell into the hole, somersaulted, and would have broken his neck when his head went between the rungs if it hadn’t been that Richard, standing at the bottom of the ladder, caught him at the last second.

Good memories. This house had once crawled with children and I was one of them. A family of nine raised here. The oldest grown and gone before I arrived. I’m the seventh. There’s a six-year gap between Clifford and me. He was born here in this house on the coldest day of the year, December 14, 1951. Three years later another baby died at birth. Mom blamed the midwife. I was born in a hospital.

These interior walls had once been covered in new blue paper, a pale blue, almost sky blue, and the room was bright and the paper absorbed the happiness of the family. I was a child running around here, and there are still atoms that were once in my body that are now in these walls, in this paper, and, I am sure, there are atoms that were once in these walls that are now in me. I am part of this place. And this place is part of me.

Home:

Does it feel that way anymore?

I examine emotions.

What does it feel like to come back here?

I stand still and listen to my heart, try to clear my mind of spinning thoughts and pay attention to the flow and ebb of stirred feelings: a happy child playing contentedly, the grief that returned at the sight of the chair, the hush of a family’s voices.

I conclude no, it doesn’t feel like home anymore; there’s too much distance, too much time between here and me. Here I was a child and the world was a different place. Now I am someone else, changed, shaped by my experiences, my successes and my failures, into the person I am today.

Today I am the searcher.

Searching for what?

For memories?

Maybe for a connection.

Connection to what?

To my beginning.

To look back at the path travelled and attempt to conceive it as a coherent line of succession; from there to here, through that and this, shaped by joy and then by grief until I am the man who stands in an old house falling down, with a floor perhaps too rotted to safely stand upon.

Is that rotted floor a metaphor for my life?

I stomp a booted foot against it, drive a heel down hard. It echoes loudly in the empty room, a solid thump. The wood beneath the floor sounds solid, different from the way decayed wood should sound. I take a step forward toward the centre of the room

and stomp again, and again I hear only the reverberations of dry, solid wood. The floor is safe to walk upon. The foundation is sound.

From outside, in the sunlight of an early September afternoon, the house in the pines appears tranquil with its sagging roofline and tarpaper shell. The remaining wooden slats nailed to hold the paper in place are grey with age; the paper itself is torn and ragged, and in places where it’s completely missing, the plank interior of the wall shows through.

The words tarpaper shack stand out in the jumble of thoughts running through my mind with all of the connotations that phrase implies: of poverty, of the fringe of the greater society, of survival, and even of a little shame.

Yes, that’s exactly correct.

My roots are in a tarpaper shack.

I feel myself stand up straighter, perhaps from a stiffening spine.

Tarpaper poor.

The paper feels brittle between my fingers and tears easily when I pull against it. A huge swath peels away from the wall and reveals shiplap planking, rich reds and browns in sharp contrast to the other sun-bleached grey boards. Beautifully aged, here is wood a cabinetmaker would give his eye teeth for, the colours and the grain, how the reds flow down the length. Thoughts of a planer and sandpaper and a little oil to bring out the lines: I could make something nice from these.

But would I?

More likely just take them home and put them in a pile and not get around to doing anything with them. And could I really tear down my childhood home and turn it into furniture? It doesn’t really belong to me; I still have brothers and it’s as much theirs as it is mine.

But I can still look. More black paper on the grass, more wood, more grains, more colours.

What the —

It rolls a couple of feet before it falls over onto its side. I just stand here, not believing. I don’t believe because it is impossible. The thing doesn’t exist. It’s something I made up, imagined, wrote down in my memories, a fragment, a figment. It never really happened, a lie I had told myself so often that it began to feel like truth.

I touch it with my foot. It moves. It is there. Despite impossibility, Clifford’s hula hoop lies on the ground in front of me.

I reach to pick it up.

Hesitate.

Do I dare?

Of course I could.

It’s just a hula hoop, a piece of plastic tubing in a circle with a stub of a handle that Clifford wired in place.

The memories come in a rush:

I

Leo Tolstoy and My Dad

Mom said that Dad sat on a wooden chair and held on. I go back in. I have to confront that chair. It could be the same one.

Dad:

He would have been eleven years old when his family emigrated from Sweden. He was the oldest of six. Next in line to him was Julius — Uncle Joe. Most of what I know about Sweden and their early life in Canada came from Joe. Joe liked to talk. Dad didn’t.

Clifford once told me he overheard a conversation between Dad and Uncle Joe. They had been arguing. Dad was saying that our family were Laplanders. I later learned that Lapp or Laplander were derogatory terms for the Sami peoples, the reindeer herders, of northern Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Russia. These Indigenous peoples were treated as harshly by the governments in their countries as were Indigenous peoples here. Uncle Joe wasn’t agreeing. Clifford said Uncle Joe’s final comment was “I am not one of those.”

We don’t know much about Dad because he didn’t talk. My older brother Clarence remembered going to the trapline with him, to a cabin about fifteen miles south along the shore of Montreal Lake: “We’d leave Molanosa walking together, and by the time we got to the lake, Dad would be a half-mile ahead. By the time I got to the cabin, he’d have a fire going and everything put away. There was a man who could walk.”

Other stories mingled in; Uncle Ben, my mother’s younger brother: “We shared that trapline at Skunk Point, your dad and me. I’d offer him a ride back to town in my truck, but he never would. Preferred to walk.”

Clarence again: “We’d be there for three days and he wouldn’t say a word. He trapped in one direction and I checked traps in another. When we came back to the cabin at night, he might say something if it was important, like if he saw fresh moose tracks or something; otherwise, not a word.”

Mom didn’t know much more about him; he never told her. And what he did, couldn’t be completely trusted. He said he was born in 1900. His birth certificate said he was born in 1898. He said that was wrong.

Uncle Joe, on the other hand, who had aspirations of living to be over a hundred like his aunt, said that he in fact was born in 1898, and that his birth certificate, which said that he was born in 1900, was wrong. Joe always wanted to be older than he was and Dad wanted to be younger.

“He lied about his age,” Mom remembered. “When we met, he said he was thirty; he was really forty. I might not have married him if I had known he was that old. I was only twenty.”

Putting it together: Dad was fifty-nine when I was born.

That’s too old to be a father. It’s not fair to the children; they get shortchanged.

So, he would have been…Let’s see, he was born in ’98, Mom was born in ’21…He was twenty-three years older than her.

They met in ’41, during the war.

If it hadn’t been for Leo Tolstoy, I wouldn’t be here.

Images of Tolstoy in Russia — or, rather, images from the Michael Hoffman movie The Last Station with Christopher Plummer — interpose themselves with those of the old house. The connection feels real even though it is quite tenuous.

The Doukhobors were called Spirit Wrestlers by the Russian Orthodox Church. The church was trying to ridicule them; instead, the Doukhobors took the name for themselves. They were spirit wrestlers. They wrestled with the established church and with the words of the Bible until they found a definition for themselves: pacifists, agriculturalists, vegetarians whose motto was “toil and a peaceful life.” In 1885 they refused conscription, burned their guns, and pissed off the tsar. At the time Russia and Britain were skirmishing along the Afghanistan border.

Tolstoy, also a pacifist who influenced Gandhi, helped the Doukhobors immigrate to Canada. When they got here, they set to work building collective farms. Canada, of course, wanted them, wanted immigrants who knew how to farm. There’s a letter from the government of Canada to the Doukhobors that promises, among other things, that if they came to Canada, they would never be compelled to take up arms.

All was good, or relatively good.

Then there was the Second World War.

And there was that other group of pacifists, the Mennonites.

Not much different from the Doukhobors, they both lived their religious principles, both groups preferred to live and farm collectively, both refused conscription. But the Mennonites were Germans. And Canada was at war with Germany. And since Canada was making life miserable for the Mennonites, it was only fair to make life miserable for the Doukhobors as well.

Those who refused conscription were given the choice of jail or work camps. Some chose jail; others chose to go to northern Saskatchewan and build a road through the boreal forest as part of the war effort. In the summer of 1941, about seventy Doukhobors were conscripted, constructing what was to become Highway 2. They lived in tents and worked on the road with rakes, shovels, and axes.

My father, and this is where we begin to know something about him, had joined the army like everyone else. However, he didn’t end up overseas. He was released from basic training. They had been marching across a wooden bridge and the bridge collapsed. The inside of his leg, from the ankle to his crotch, was ripped open by a spike, and the wound would not heal at the knee. I never saw it. Mom said the scar looked like a piece of clear plastic.

By the time I got into the armed forces in 1975, we were told during basic training that

when we marched across wooden bridges, we were to break stride because if we all brought our feet down in unison, the vibrations could cause a bridge to come apart.

We don’t know where my father was for the two and a half decades between when he left the family homestead at about the age of fourteen to go work as a farm labourer to when he was released from the military because of his wounds. He came back to Saskatchewan and showed up here in the North as a foreman over the Doukhobors.

His mother died just before he left home. He said his father was incapable of looking after his siblings so he took them to the neighbours’. The 1930s happened. He told a few stories, mere glimpses of his life, of riding the rails, travelling across Canada looking for work: “I saw these people, Indians, they had a big pot and were cooking. I asked if I could get something to eat. They all had their heads down, kinda ashamed, I guess. One of them says to me, ‘We’re eating gophers.’ I said, ‘If you can eat it, I can eat it.’”

But other than these few snapshots, there’s a big chunk of his life that we cannot account for, that he never spoke of, not because he had something to hide: he just wasn’t a man of words.

So, if it hadn’t been for Leo Tolstoy’s helping the Doukhobors, the Doukhobors’ immigrating to Saskatchewan and being forced to work on a highway in the North, and my father’s finding a job as their supervisor and meeting my mother, I wouldn’t be here.

Mom and Baby Brother Stanley

The chair, the three-legged chair, isn’t talking either. It stands mute. All I have with me in the house is Clifford’s hoop over my shoulder, Mom’s stories, and dim memories.

Mom said her father was working with the surveyors, going ahead of the highway construction crew, showing them the way through the forest. Dad met Grandpa at work and came over for tea, and that’s how they met.

Clifford

Clifford