- Home

- Harold R. Johnson

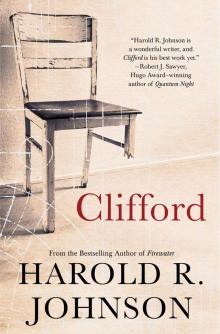

Clifford Page 14

Clifford Read online

Page 14

I stood outside, over and away from the doors, waiting for the hearse to arrive with the coffin with my brother, with the guest of honour, with our reason for being here, loggers and miners dressed in unfamiliar suits and ties.

Six brothers as pallbearers, black ribbons pinned to our sleeves, carry the coffin from the hearse into the church, and as we go through the doors, I wish there was another way of doing this ceremony of offering Clifford to the sky. I have no memory of Clifford’s ever walking into a church. He shunned organized religion, preferring rationality and his own ways of knowing. The only way to get him in was to carry him.

Repeatedly in the days between, brothers told brothers, “Clifford would have wanted . . .” His sons were told, “Your dad would have wanted . . .” Have a good life, remember the good times. Decisions were made based upon what Clifford would have wanted; all except this — this Christian ceremony of funeral. No one bothered to ask themselves whether he would have wanted this. This is for the people, for the aunts and cousins, for Mom.

He didn’t resist. He didn’t kick at the casket and refuse.

We took him through the funeral rites of the Anglican Church on the rock beside Lac La Ronge, then we six brothers wearing black put him again in the hearse for the fifty-mile ride back here to Molanosa, to bury him beside Dad in the graveyard where all the other gone relatives have markers over their bones.

I feel an ache at the memory, wriggle deeper into the hollow of the tree roots, pull the sleeping bag tighter around me, not because I am cold, but just for the closeness, for the comfort.

One of our conversations when we were both still single, before we each married and made children and our lives became less entangled with each other and more wrapped up in our own families: I had spoken brazenly, arrogantly even, regurgitated Nietzsche: “God is dead.”

“What are you reading?” Clifford reached over and flipped up the cover of the book in my hands. Thus Spake Zarathustra. “You be careful with that.”

Why should I be careful with it? It was from his bookshelf.

I closed it, set it on my lap. The morning of reading — Clifford in the armchair, myself stretched out on our couch, a few hours of early-day silence broken occasionally as one or the other of us rose to go to the coffee pot, refill a cup, and return nose-first into paper and pages — was over. Now for conversation.

It was a common routine between us. To read, then discuss. We had been here many times before. I waited. I had started the conversation part of the morning, let him answer. Was God dead or not?

He began with something not only uncharacteristic of him, but also something he had insisted was the weakest of all arguments. Instead of confronting Nietzsche’s ideas, he attacked the man.

“All of his ideas come from his fear of death.”

I waited. There had to be more to come.

But it turned out to be more than a pause in conversation. I waited while Clifford went to the coffee pot. There was a cup of black at the bottom. He picked it up, swirled it, looked through the glass at the colour and thickness of it, put his nose over the rim and smelled, then poured it down the sink and carefully prepared a new pot.

While we waited for a new brew, I rinsed my cup in anticipation, had time to think through the minutes of silence broken only by the burping of the electric coffee maker. Nietzsche said God was dead because he was afraid of his own death. I tried to connect the two concepts, but the connector refused to show itself.

The last drips plopped into the pot. Clifford first removed the lid and stirred because the stronger coffee is always at the bottom and the weaker at the top. It was either an act of fairness that we each got the same strength brew or he didn’t want the weak top cup.

Mine black with half a teaspoon of sugar just to cut the bitter; his with milk and a whole spoonful of white refined.

Back on the couch, my feet flat upon the floor, I tasted, a sip, strong, black, earthy, with a hint of sweet, held the cup with two hands, felt the warmth with my fingers.

Clifford back in the armchair, only the heel of his right foot on the floor, his legs outstretched, crossed, relaxed. He tasted his once, then again, before putting the cup aside.

I lost patience. “So why was Nietzsche afraid of death?”

He didn’t answer the question directly. Instead, he looked at me, directly into my eyes.

A staring contest?

Maybe.

I never lose these. I stared back into his, into the green and the blue and the grey, that blend that defied description. But it wasn’t a competition. He was looking into my soul.

“You know,” he began, “you have always known — ever since you came into this world, you have known. There is a truth, an absolute truth, and you have been aware of it all of your life. You have a sense, an understanding that has always been there that tells you one thing. That one thing is that you were destined for greatness. It is so much a part of you, and has been part of you for so long that you don’t listen to it anymore. It has become just background noise in your consciousness.

“Nietzsche lost contact with that knowing. To put it poetically, he stopped listening with his heart and tried to resolve everything with just his mind.”

I interjected, “What’s wrong with rationality? Shouldn’t we put emotions aside?”

He held up his hands, palms toward me, indicating that I should wait, he hadn’t finished his thought.

“To answer the really big questions we must rely upon all ways of knowing. You can know things with your mind. That’s the most common way of knowing. But you can also know things with your body. Have you ever had the hair on the back of your neck stand up, or felt a shiver run down your spine?”

I nodded. Of course I have, everyone has.

He continued, “That’s your body’s way of knowing, and quite often it knows things before your brain. You also know things intuitively.”

He raised his cup but didn’t drink yet.

“We’re related to the animals. Geese fly south in the fall, not because they rationalized that winter is coming and they are going to freeze if they stay. They know in a different way to flock together and follow the same flight path every year. A baby knows intuitively that when a nipple is placed in its mouth for the first time, it should suck. You’ve been in situations where you just knew something wasn’t quite right and got yourself the hell out of there before the shit came down.”

“Yeah, but is that intuition or is that the subconscious?”

“If it’s subconscious,” he answered, “knowing without knowing, or knowing without being aware that you know, can we really call it rational? If it’s really your brain doing things, calculating, running a subprogram hidden from you, where is that taking place? Where in the mind does that happen? Which neurons are firing? And why is it able to do those calculations so much faster than the conscious mind?”

I didn’t have an answer.

“I’m suggesting that the subconscious mind and intuition are either the same thing or they’re closely related. Either way they’re not rational. They’re simply other ways of knowing.” He tasted his coffee.

“So what’s this have to do with Nietzsche’s being afraid of death?”

“So . . .” He put down his cup. “Nietzsche was no different from anyone else. He knew things he couldn’t explain, things that scared him. He knew, like everyone knows, that he was going to die and that the worms were going to eat him. But he refused to ever talk directly about that; he refused to allow himself to even think about that, because if he did, if he accepted the inevitability of it — that he was going to grow old, become weak, slowly lose his sight and his hearing, become impotent, wrinkle, and lose his teeth — then, rationally, his life was meaningless. The only way he could put meaning into his life rationally was to deny the inner voice, to either simply not listen to it or say that it didn’t

exist.

“That inner voice, that intuition or subconscious or whatever else you want to call it, that thing that tells you that you are destined for greatness — that’s your soul whispering in your ear. It’s telling you to sit up and pay attention. It’s telling you, you don’t have much time left, get on with it.”

“Get on with what?”

“Get on with living. That’s what you’re here to do.”

“So you don’t think Nietzsche was living as fully as he could.”

“No, that’s not what I am saying. I’m saying he denied his inner voice. If he had listened to it, paid attention to what it was telling him, tried to find where that voice came from, he would have to conclude that it came from nature, or super-nature, or spirit — and he wouldn’t have been able to deny God.

“Here’s the difference. Nietzsche, and I don’t remember if it’s in there” — he pointed at the book on the arm of the couch beside me — “or if it’s in his other works, argues that man evolved from monkeys. If we evolved from monkeys, then man is just another animal with a bigger brain. There is no inner voice to listen to, and morality becomes something we made up so that we wouldn’t exterminate ourselves, rather than something we were born knowing. If we learned our morality, then we came from monkeys. But if we are born knowing right from wrong, then we came from the stars. We either evolved here, came from chance collisions between molecules in a primordial soup and spontaneously became alive, or our origin is much grander than that.”

“But if we came from the stars, we had to originate somewhere.” I knew that we were getting off-topic, straying from the original thought. I simply needed to challenge him on some point, or I would have to sit passively and be lectured to.

“Origins . . .” He leaned a little forward. “I showed you time is not linear. Remember time waves?”

I did.

“There is no beginning and end,” he continued. “There doesn’t have to be a specific point where life began. It could just as well be eternal. If life is a product of the universe and the universe is truly infinite, then we are chasing a rabbit down its hole and entering a world of absurdity when we insist upon only one way of knowing, that being the sterile rational and the denial of all other knowledge.”

He stopped. Looked down for a full second, his coffee forgotten on the table beside him.

“It’s about that message.” He started again, his voice softer. “You know that you were destined for greatness. It’s written in your DNA, it’s your soul whispering to you, it’s your intuition, or your subconscious, it’s everywhere except in your rational mind. But you are not alone with that; everyone has it. Some people interpret it to mean that they should go to war and become heroes; some think it means that they should accumulate all the wealth and power that they can; some use it as an excuse to subjugate others. We have a rational mind and an internal message. Our task is to use both, keeping it clear that we are going to die, so wealth and military power and all those other immediate measures of self-worth are inadequate. Greatness must be greatness of spirit, and since all people have the message, it must mean the greatness of humanity and not of the individual. For humanity to become great and achieve its potential, we must individually become great and continue to strive against barbarism; we must seek the end of war, the end of inequality, the end of useless suffering.

“You were born knowing that you were destined for greatness. Everyone is born with that same message written in their DNA. It’s what kept the Indians walking on the Trail of Tears. It’s what has kept us going despite everything. That kid you see on television with the extended belly and the flies crawling all over him, and they’re trying to get you to send money to save him — he has the same message. That’s why he stays sitting up, why he doesn’t just lie down and die. It’s an irrational sense of purpose. Most people have it educated out of them, or, like the kid on television, blocked by trauma, but we all have it. We just have to learn to listen to it again.”

* * *

I sit up under the tree, pull myself from the comfort of the hollow between the roots, and look up at the sky, at the stars, at those pinpoints of distant light, light that travelled for millions of years so that I could look up tonight and see it, and I wonder where he might be in this moment and whether he has a new understanding of his own greatness.

Time Heals All Wounds

The next sound I hear is the buzz of mosquitoes. There’s a bit of light in the northeast, a little before sunrise, five-thirty, maybe six. Now I wish I had put up my tent with the screen mesh to keep out the bugs. I lie still for a while, eyes closed, sleeping bag over my head, but it’s too hot and stuffy and I’m not going to get back to sleep in any event; may as well get up.

A fire.

A handful of red pine needles — they burn as if they were made out of gasoline — gets it started, a few bigger twigs to keep it going. And once it’s flaming nicely, some moss to make smoke to chase the mosquitoes away. I stand in the thick of it and let it cover me until I smell like burned peat, a more natural insect repellent.

Coffee first, while the fire has a good blaze. It boils quickly.

Then bacon in a cast-iron frying pan. The fire is still too hot even for bacon, and I take it off the flames. The residual heat in the cast iron is sufficient to brown the half-dozen slices bouncing in their own grease.

Then, when the fire has died down some, sliced potatoes until they’re beginning to brown before I add a handful of chopped mushrooms and onion to complete the fancy hash browns.

And finally, when only coals remain and the frying pan has been scraped clean again, three large eggs that slowly turn white before I cover them with a lid and wait patiently, sipping on hot, strong, black coffee.

A good breakfast to start a new day. The eggs are a little crispy around the edges, but the bacon turned out perfectly, nicely browned, and the potatoes and onions and mushrooms have a nice smoky flavour. Bread toasted on a stick and a couple of thick slices of cheddar, just to give it a bit more substance.

While I eat, sitting cross-legged on the ground with the plate on my lap, my coffee cup beside me, the early light of the new day in the tops of the pine, I begin thinking about time. Is it really the way Clifford told me? Or did he just make all that stuff up? Gravity, black holes, space waves, and whirlpools.

Time.

He’d said time travel was impossible, you can’t go forward and backward through it. But he could change the rate of time, speed it up or slow it down. It was, after all, only another wave like space, and if one could be modified, so could the other.

I sip my coffee. Let the thought continue uninterrupted.

Time waves bounce off the surface of the earth and cancel each other out, so time runs slower closer to the surface than higher up. We know this because global positioning systems, GPS, must calculate the time difference between the satellite and the earth, or else the position it gave would be off by several yards.

So maybe he was on to something.

People in emergency situations sometimes describe their experience as though it happened in slow motion. Clifford said that was because they slowed down their personal time. They were still reacting at their normal speed and, to them, it seemed like everyone else was going slower.

So, if he could, like he said, control time…

Why didn’t he?

He could have slowed down time and the truck coming across the line would have appeared to be moving in slow motion. He could have gotten out of the way.

Unless…

More probable. He had his time set faster.

“If I need more time, I adjust it so that it runs faster. To everyone around me, it seems like I am moving real slow. It comes in handy when I need extra sleep. I speed up time before I go to bed. I get a full eight or nine hours of sleep, but to the rest of the world only three hours have gone by.”

&n

bsp; Is that what he was doing? He had a long drive. He’d spent all day packing everything he owned into his truck. He would have been exhausted before he left. Did he speed up his personal time so that the trip wouldn’t take as long?

Is that what happened?

Did the drunk guy going north at one time meet Clifford going south at another time, and one or the other miscalculated the time and speed of the other?

Or was it simply that his truck was so overloaded that he couldn’t get out of the way? They had cleaned up the crash site, hauled his truck away to the salvage yard, and brought everything he had to my house. He’d taken pride in his ability to pack. He could fit more things into a truck box than anyone else. The secret, he said, was garbage bags. They fit together without air spaces between. Whatever method he used, the clean-up people needed a three-ton truck to carry everything he had packed in the back of his half-ton.

They came and unceremoniously raised the hoist and dumped it all in my driveway. There was no reason to be careful. It was all broken and rain damaged, and there was very little left for me to salvage. Smashed televisions, the oscilloscope, meters, wires, and transistors, and clothes and books and papers all wet and stuck together.

Maybe when I was packing it all up to take to the garbage dump, I didn’t recognize it. What would a time machine look like, anyway?

Maybe that was best. Like he said, the world wasn’t ready for it. It would cause too much trouble. Imagine if an Olympic runner had access. They could cheat by adjusting their own time slower so that they raced against people who were in slow motion. Or even worse, if a government got a hold of it and put it on one of their missiles. The country being attacked might not have time to react.

Clifford

Clifford