- Home

- Harold R. Johnson

Clifford Page 13

Clifford Read online

Page 13

“You know about entangled particles?”

I sort of did, but…“You’re jumping all over the place here. One thing at a time. I can see how parallel stories work with religions that have the same roots with a monotheistic god and that each believes they alone know the one truth. I can even accept that workers and bosses need each other, but science…Shouldn’t that at least be a consistent story?”

“Consistency doesn’t need to be singular.” He’s smiling. “Entangled particles. Remember what Einstein called ‘spooky action at a distance.’”

I remembered. Cause two particles to become entangled and then separate them, and what you did to one immediately caused the other one to react, and the reaction happened faster than the speed of light. “So now you are going to tell me that the particles are stories,” I guessed.

“Sort of.” He paused. “I had thought that for a while. No, the particles are not stories but they are parallel. It’s a good analogy of parallel stories but it doesn’t quite capture it. I just figured out what is going on there before you interrupted my thoughts with your questions. Here’s what I think. Remember how I was telling you that the universe is expanding because it is surrounded by a void and the void is stretching it and by stretching it, it’s putting energy into the universe, and when you have enough energy, it becomes matter?”

He was completely changing the subject. But, yes, I remembered.

“Well, it doesn’t quite work out. The stretching alone can’t account for all the energy. It takes a lot of energy to become matter. E=mc2 means that you have to move mass at the square of the speed of light before it becomes energy. Say it the other way, and you need energy equal to the square of the speed of light to make matter. It’s too much. One spoon of sugar contains enough energy to flatten a city the size of New York. That’s where the idea of the atom bomb came from.

“If all matter used to be energy, there’s too much matter in the universe. There couldn’t be that much original energy. So what I think is going on is those entangled particles are actually the same particle in two places at the same time.”

“Whoa, whoa,” I interrupt. The ramifications are too big. If every particle in the universe was entangled with another particle somewhere else in the universe and they were the same particle, then the universe has only half the mass we think it has. “Things can’t be in two places at the same time.”

“Sure they can, if we introduce the idea of a void. Remember that in a pure void an object would be everywhere and nowhere at the same time.”

“But that’s only in the void that surrounds the universe and in black holes. The universe is not a void.” I ease off on the gas pedal. I can’t drive fast and think all this through at the same time.

Clifford’s voice shows his excitement. He obviously just figured this out while we were talking. It’s as fresh to him as it is to me. “If the only voids are black holes and the one that surrounds the universe; but what if each atom was a quasi-void?”

“Quasi-void?” I ask. “Wouldn’t it be a void or no void? Something or nothing?”

“No, what we are dealing with is space. That’s the thing. That’s the magic. Space does all the work. Through it, energy becomes matter and things have position. But if space is a wave, like I think, then when we change its frequency it becomes something else, like light or gamma rays or whatever. Whenever we put energy into space, space changes. So what’s going on inside the atom?”

I know the answer. “Positively charged proton, neutrally charged neutron combined in a nucleus, and negatively charged electrons in orbit around the nucleus.”

“Wrong,” he replies. “That’s what they taught you at the mines when they were trying to explain nuclear radiation. It’s a simple way of looking at the atom so that you can say alpha radiation is caused by neutrons, and beta radiation is caused by protons, and gamma radiation is pure energy from the nucleus. But that’s not how it really works. The proton and neutron do make up the core of the atom, but the electron is not in orbit like a planet around the sun. The uncertainty principle says that the electron is everywhere and nowhere around the nucleus at the same time. You can know its location or its velocity but never both at the same time. I think the reason is because of the incredible amount of energy in the atom. Square the speed of light to give the proton and neutron mass. All that energy has displaced space. Remember you need space to have place. So where the electron exists is in the quasi-void where space has been pushed back by the atom’s energy.

“And if I am right about this, then every atom has a tiny void in it, and because position can’t exist in a void, a particle can be in two places at the same time. And not just two places. There’s no reason why it couldn’t be in multiple places at the same time.

“Hey, you know what. If voids can exist at the core of an atom, there is no reason they can’t be everywhere.” He is obviously thinking this up as he’s speaking. It comes through in his eagerness. “Sure, that would explain the particle-antiparticle problem. There should be as many antiparticles as there are particles in the universe. It’s baffled science as to what happened to them. Voids explain where they went.”

“Hold on, hold on. Where are all these voids? Are you talking about black holes?”

“No,” he answers. “Space doesn’t have to be continuous. If there were tiny voids throughout it, we wouldn’t notice. They would be undetectable to us because they are nothing. There is no reason why half the space between you and I” — he waves his hand in the air to show me the space between us — “isn’t made up of little voids that we can’t perceive.

“Yeah, this makes sense. The difference between a particle and an antiparticle is simply that particles exist in space and the unique properties of antiparticles only allows them to exist in voids.”

He leans back and thinks about what he just said. A thin smile shows. A moment later he says: “Imagine…Somewhere else in the universe you and I are driving along, having this same conversation. We are there and here at the same time and it doesn’t matter.”

And now he is somewhere else in the universe and I am here. Maybe we were parallel stories. What I did to him, he did to me. Even if we were not parallel stories, we were entangled particles. There is no asking Clifford for a solution to the riddle. It’s too late for that. Any chance at an explanation ended with a knock on the door.

Two Hours

September 1, 1985, at about nine o’clock in the morning. I never saw it coming.

Night shift was over. Abe Weins and I were playing backgammon, smoking a bit of homegrown, and drinking homemade crabapple wine. We had been friends for a long time. We were both heavy-equipment operators for Cameco Corporation at the Key Lake Uranium Mine. I mostly drove a truck, hauling waste or ore out of the open pit, sometimes on a dozer or grader or loader or something to break up the monotony of mining production. The work was one week of twelve-hour shifts at the mine and then one week at home. It was a civilized rotation. Before working for this company I had put in many three-week shifts followed by one week off. I had also worked five-, seven-, and eleven-week rotations. Week in/week out was almost a holiday.

Backgammon: a dollar a game and the doubling cube; we kept a score sheet and paid up at the end of the week. Some weeks he owed me twenty bucks; another week and I owed him twenty. Backgammon is a game of chance.

Abe grew the marijuana on his farm. He liked to say, “Pure organic, nothing added to it other than a bit of pig shit.” He also made the wine, was proud of his brewing skills and his Mennonite upbringing that didn’t allow him to spend a penny that didn’t need to be spent.

We played in my room because I had a better sound system. We were listening to either Huey Lewis and the News or Mark Knopfler and Dire Straits. Kept the volume down, kept our voices down, some people go straight to bed after night shift. We preferred to party a bit, go to sleep a little later so that we woke

up just before we had to go back to work.

We were upstairs in E wing of a three-hundred-man modern camp that was quite luxurious. Someone had nicknamed it Hotel California; you can check out but you can never leave. We were laughing and throwing dice when the recreational director knocked on the door.

He’d been sent upstairs by Garnet Wipf from Personnel.

When I got downstairs, Garnet explained: “I didn’t want to come up on my own, never know what you might have been doing up there, whether you had a bottle or not.” It was understood. If Garnet caught me with a bottle, he would have to take disciplinary action and I could be fired. Everyone knew that Garnet Wipf would fire you. He was the most hated man who ever walked. You’d wait a long time to hear a good word about him at the Key Lake site. Up until that day I’d had no contact with him, had no judgement of him.

“What’s up?” I hoped I wasn’t slurring my words, hoped my eyes weren’t too bloodshot, not too glazed.

“Bad news. We got a call from the RCMP in Pine House. They want you to give them a call.”

“Did they say what it’s about?”

“No, just that it was very important and they want you to give them a call.”

The phones in the camp didn’t work. The Key Lake mine site was about 125 miles north of the nearest community, the village of Pine House, which was itself already remote. Phone service that far from the settled South of the province was at best sporadic.

“It’s okay, you can use the phone at Administration. We’re on a different line from the camp’s,” Garnet offered.

The administration building was over with the mill operations, about a mile from the camp. I phoned the RCMP in Pine House from Garnet’s office. He shut the door for privacy.

“Hello. This is Ray Johnson up at the Key Lake site. You guys wanted me to give you a call.”

“Yes, Ray. We have a message from the Prince Albert detachment. Someone in your family has died.”

“Who?”

“I’m not sure, and I’m not going to say until I am sure. Please stay where you are and I will call you back when I know.”

Then the negotiations began.

Someone in my family —

I had two children, Michael and Harmony. Mike was eight; Harmony, four. We lived in the little town of Saint Louis beside the South Saskatchewan River. It was a fast-flowing river…

There was a street in front of the house. There was traffic on that street. Mike and Harmony sometimes played on that street…

Please God. Not my children.

It was a gravel street.

Mom lived across that street. She’d come to visit after we bought our house there. She liked the community, and we helped her to get into a low-rent apartment for seniors right across the street. I couldn’t get the image of that strip of gravel bounded by sidewalks out of my head. Mom’s health wasn’t that good, and she liked to walk down to the pub on an afternoon…

Please God. Not my mom.

My brothers Garry and Donny had been planning a hunting trip up the Bow River…

Oh God. No, not my brothers. Please.

Clarence was working, driving truck…

Jimmy was mining…

Richard was mining…

Stanley was working for a crane company…

Possibilities.

Industrial possibilities.

Industrial probabilities…

Shelly, my wife.

Our marriage wasn’t going so well.

I married her because I got her pregnant and it was the right thing to do, the honourable thing. But I did love her. I really did. We stayed together for more than just the sake of the children.

But her sister had committed suicide and Shelly wasn’t happy…

Who?

Someone in my family.

Who?

It was two hours from the knock on the door until the return phone call from the Pine House RCMP. The negotiations had been intense.

God is a bastard to negotiate with.

He had me cornered, nailed down. I’d fought hard, battled with him, all of my determination and will, and in the end…

In the end I’d traded them all, every one of them: Mom — my brothers — Shelly — every one of them, for my children.

Please God, anybody — but not Harmony or Michael.

Two hours.

Two hours from when I found out someone in my family had died — two fucken hours until I learned who in my family had died.

Clifford.

“Oh fuck!”

Clifford was killed in a car accident.

“Fuck. Now what? Fuck.” I wanted to shout. I wanted to punch someone, something. “Now what?”

“I’ve chartered a plane to fly you out. It’ll be here in about an hour. Come on, I’ll drive you back to camp so that you can pack.” Garnet leads, directs. At one point he said, “I’m not trying to boss you around. I know that you’re in shock and you’re having a hard time making decisions right now. I’ll walk you through it. Now you have to go upstairs and pack your things. You’re going home. Where do you fly out to?”

“Prince Albert. Yeah, Prince Albert. But my truck’s not there. I loaned it to the people I have working for me.”

I was such a workaholic that I had been trying to run a fence post–cutting operation on my week out and had a couple of Shelly’s cousins working for me.

“Not to worry. My truck is at the Prince Albert airport.” Garnet handed me a set of keys. “Just leave it where you found it.”

I also didn’t have any money. Payday wasn’t until Thursday. I hadn’t brought any cash to camp with me because I wouldn’t need it.

Garnet dug in his wallet. “Here’s forty bucks.” He handed me two twenties. It was the last he had.

This was from the asshole whom everyone in camp hated.

* * *

It’s a hard memory to go through. Was it already a week? One whole week since I negotiated with God. Fly out — meet up with my family — all the brothers, now there are only six of us, two sisters, nephews, and nieces. We gather around Mom. She says she has buried her husband, both her parents, brothers, and a sister, but the hardest thing she has ever had to do was bury one of her children.

A drunk driver, they said.

Clifford was on his way to Yorkton to go to school. Finally, he’d found a job, something that he wanted to do. There are several local radio stations across northern Saskatchewan; each little community has its own. He’d scored the position of being the person who maintained them. He just had to go to school for nine months for an upgrade.

It happened at the S curve just north of Prince Albert. He was only a few miles away from the campground where he intended to spend the night. His three sons were in the truck with him: Clifford, Brian, and Daniel, thirteen, eleven, and nine. The oldest boy, Clifford, is still in an induced coma, his face smashed in. Brian and Daniel weren’t physically injured.

Slam!

You’re knocked on your ass.

Unprepared.

There’s no fixing something like that. You can’t go back and make it better.

I didn’t get any warnings, no premonitions. A bird didn’t fly into my house. A woodpecker didn’t come and warn me. Nothing. I was playing backgammon, smoking pot, and drinking homemade crabapple wine. It was a beautiful day, sunshine, the leaves were getting ready to change and I didn’t see this coming.

They wouldn’t tell me who the other driver was. Mom’s instructions, my youngest brother, Donny, and I were not to be told: “I lost one son, I don’t want to see any of the others end up in jail over this.” When I recognized her rationale, I didn’t ask. If I didn’t know, I didn’t have to do anything about it. It’s best that way. And Mom was right. We had enough to take care of.

Six brothers

as pallbearers.

But the ceremony of funeral couldn’t heal all the hurts.

It happened too fast.

I am as guilty as the rest of them.

My “work hard, fight hard” military attitude had come between Clifford and me. I was as pissed at him as everyone else. What the fuck was he doing? He had three sons to look after and wouldn’t get a job, lived on welfare. He was an embarrassment, and we all took turns telling him so or letting him know in other ways that we didn’t approve.

Then, when he got a job…

And he was happy again…

And his life had purpose and he was going to do something…

And it was too late to say sorry.

Clarence had been the hardest on him, the most outspoken and direct, and when Clifford died, it hit Clarence the hardest. By the time it was over, Clarence had a very good understanding of Clifford’s situation. We’d talked yesterday, Clarence and I, about Clifford’s depression at his wife’s running away and his subsequent inability to maintain employment. I’d never seen Clarence cry before.

It was a hard thing to watch.

Fear of Death

Sorrow pulls at me. It tries to find the empty space. But I have had enough. I have given my grief all it needs. I am drained and there is nothing left to drag out of me. In the days between the phone call and the burial yesterday, family came together and we held each other up. My wife, Shelly, held me, the door to our bedroom closed so the children would not see while I cried, while I sobbed huge, wet, snotty sobs, an ache in my throat and a heavy weight in my chest. The physical manifestations of grief bend the spine; I could not stand up straight. I could not raise my head. Grief dragged at my feet until I shuffled. It robbed food of its flavour, and I ate the sandwiches at the wake only because I needed their energy.

The first days were a struggle, reeling, unbelieving, even denying, expecting any minute to hear Clifford laughing at this joke that has no punchline. But he doesn’t laugh, and the reality of what is going on builds with the view of each relative’s tear-stained face. Mom was the most experienced at grief; she had lost her husband, both her parents, her favourite brother, and her little sister. We were standing in front of the church, getting ready to go in, and again she said, “This is the hardest, losing one of your children.” Then she took my sister’s arm and walked with her, shared her strength.

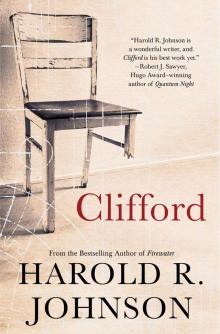

Clifford

Clifford